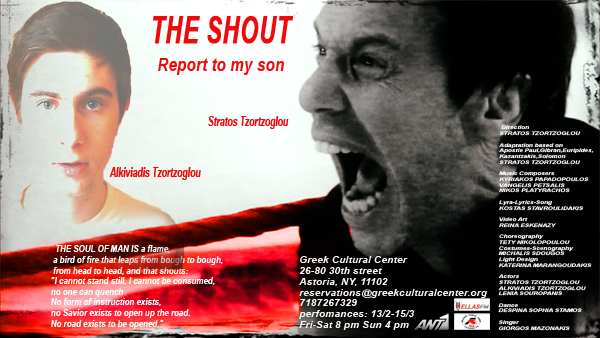

THE SHOUT a musical (oratorio) performance based on Nikos Kazantzakis‘ The Saviors of God / Askitiki – Report to Greco. World tour starts in New York and for the period February 12 – March 15, the show will be staged at the Greek Cultural Center, with subsequent destinations as San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago in the States and then in Montreal and Toronto in Canada and Sydney and Melbourne in Australia. Spring 2015 the show will be staged in Athens with subsequent destinations Crete and Cyprus. As Kazantzakis himself says, “You shall never be able to establish in words that you live in ecstasy. But struggle unceasingly to establish it in words. Battle with myths, with comparisons, with allegories, with rare and common words, with exclamations and rhymes, to embody it in flesh, to transfix it! God, the Great Ecstatic, works in the same way. He speaks and struggles to speak in every way He can, with seas and with fires, with colors, with wings, with horns, with claws, with constellations and butterflies, that he may establish His ecstasy”. SG takes the form of a prophet’s plea to change our conception of God so that we can live better. Kazantzakis assumes there’s a difference between the esoteric and the exoteric, between the unknowable mystical truth and the mere masks of God. And Kazantzakis’s vision of divinity is quite peculiar. It reminds me of the myth of Sisyphus. Whereas the mainstream monotheistic idea is that God is a flawless person, Kazantzakis says that God is imperfect, that he’s a vagabond who struggles between two eternally opposing forces, one pulling him down into entropy and lifelessness and the other raising him up to freedom

My own body, and all the visible world, all heaven and earth, are the gravestone which God is struggling to heave upward… God struggles in every thing, his hands flung upward toward the light. What light? Beyond and above every thing!… God cries to my heart: “Save me!” God cries to men, to animals, to plants, to matter: “Save me!” Listen to your heart and follow him. Shatter your body and awake: We are all one… So may the enterprise of the Universe, for an ephemeral moment, for as long as you are alive, become your own enterprise. This, Comrades, is our new Decalogue. “He struggled, therefore, with the only tools he had, pen and paper, striving to purify his style, dreaming of a new theology, a new religion of political action in which the dogmatic, teleological God of the Christians would be dethroned to be replaced by dedication to the theory of an evolutionary and spiritual refinement of matter.”

These two armies, the dark and the light, the armies of life and of death, collide eternally. The visible signs of this collision are, for us, plants, animals, men. The antithetical powers collide eternally; they meet, fight, conquer and are conquered, become reconciled for a brief moment, and then begin to battle again throughout the Universe – from the invisible whirlpool in a drop of water to the endless cataclysm of stars in the Galaxy. Even the most humble insect and the most insignificant idea are the military encampments of God. Within them, all of God is arranged in fighting position for a critical battle. Even in the most meaningless particle of earth and sky I hear God crying out: “Help me!” Contributors DIRECTOR: Stratos Tzortzoglou DRAMATURGY: Stratos Tzortzoglou, Tsimaras Tzanatos VIDEO ART: Reina Eskenazy with Scenes from Angelos Spartalis‘ films: 37 Memories, Wishes, From the Earth to the Moon MUSIC COMPOSER: Kyriakos Papadopoulos, Vangelis Petsalis , Nikos Platyrachos CHOREOGRAPHY: Teti Nikolopoulou SCENOGRAPHY: Michael Sdougos SINGER: Natalia Soledad Petsalis, sings Nikos Platyrachos‘ song To Dakri tou Psiloriti (Psiloritis’ Tear). CRETAN MANTINADA: Kostas Stavroulidakis

Ασκητική, ένα πρώιμο έργο του Καζατζάκη, ενώνεται με αποσπάσματα από την Αναφορά στον Γκρέκο, έργο της ωριμότητάς του. Μαζί αποτελούν μια κατάθεση ψυχής. Μια Κραυγή συνειδητότητας και αποκάλυψης ότι τίποτε δεν είναι όπως φαίνεται. Ρόλοι. ύλη, σχέσεις, συνθήκες , είναι όλα πλάσματα του νου. Η αλήθεια εδράζεται στο σώμα και είναι αυτό μόνο που μπορεί να σε φέρει στο εδώ και τώρα, στο Είμαι της ανθρώπινης ύπαρξης. Η ενοποιητική προοπτική που προσεγγίζει ο Καζατζάκης τη ζωή, δηλώνει ότι ο Θεός δεν είναι έξω από εμάς αλλά ζει μαζί μας και ο γιος του Ανθρώπου έχει οπωσδήποτε μια αποστολή. Να συνεχίσει τον αγώνα του συνειδητά και συνδεδεμένα με τα πάντα γύρω του. Ο ασκητής του Καζατζάκη είναι ανθρώπινος, σωματικός, αδύναμος, ατελής, απροσάρμοστος αλλά πάντα ζωντανός και αγωνιστής. Στην παράσταση το κείμενο προσεγγίζεται σωματικά. Χορογραφικά, καθώς …ο χορός σκοτώνει το Εγώ… Σε ένα άλλο επίπεδο “ζουν” οι μνήμες, οι οποίες σαν εικόνες – θραύσματα υπάρχουν μέσα στον ήρωα, όπως η νεότητα υπάρχει σε κάθε ηλικιωμένο. Ο ήρωας πρέπει να αποποιηθεί το Εγώ του να σπάσει το είδωλο και να κατανοήσει την ουσία της ύπαρξής του, να βάλει σε τάξη το χάος για να ξαναπάει πάλι σε αυτό, ώστε να μπορεί να κοιτάξει, στο μέλλον, πίσω του χωρίς αποστροφή, έχοντας εκπληρώσει το χρέος του. Να ζήσει συνειδητά. Χωρίς να περιμένει τίποτα από κανέναν.

Και αυτή η αποστολή είναι τόσο αναγκαία που πρέπει οπωσδήποτε να τη δώσει σα σκυτάλη στον επόμενο αγωνιστή κι αυτός στον επόμενο κι αυτός στον επόμενο κ.ο.κ. Σαν ένα γράμμα κληρονομιάς στο ΓΙΟ. THE CRETAN GLANCE The Spirituality of Nikos Kazantzakis L. Michael Spath, D.Min., Ph.D. OPENING READING – From Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises A vehement Eros runs through the Universe. It is harder than steel, softer than air. It cuts through and passes beyond all things, it flees and escapes. It is a Militant Eros. Behind the shoulders of its beloved it perceives mankind surging and roaring like waves, it perceives animals and plants uniting and dying, it perceives the Universe imperiled and shouting to it: “Save me!” Eros? What other name may we give that impetus which becomes enchanted as soon as it casts its glance on matter and then longs to impress its features upon it? It longs to merge with the other erotic cry, to become one till both may become deathless. It approaches the soul and wishes to merge with it so that “you” and “I” may no longer exist. It smashes the duality of mind and body, to merge all breaths into one Divine Monad. In moments of crisis this Erotic Love swoops down on human beings and binds them together. It is a breath superior to all of them, independent of their desires and deeds. It is the Spirit, the breathing on the earth of what human beings call God.

And it comes in whatever form it wishes – as dance, as Eros, as hunger, as religion, as art, and does not ask our permission. THE DIVINE EROTIC CRY “My entire Soul is a Cry, and all my work a commentary on that Cry,” he writes at the beginning of his spiritual autobiography. “That which interests me is not humanity, the earth, or heaven, but the Fire that consumes humanity, earth and sky.” He divides his life into four stages, each identified with one of “four great souls”: his life begins with a traditional embrace of the Orthodox Christ, but this was too constricting; so he turned to the Buddha’s inner peace, but this was too flesh- , too world-denying; third, Lenin’s Marxist revolutionary activism, but this was devoid of the transcendent; so finally, he embraced Odysseus (Ulysses in the Roman myths), but transcending Homer, a heroic Odysseus who “develops the courage and integrity to embrace the great contradictions of human existence, its joys and tears, without flying into an imaginary world.” (Zarathustra) Kazantzakis writes: We see the highest circle of spiraling powers, and have named it God. We might have given it other names: Abyss, Mystery, Absolute Darkness, Absolute Light, Matter, Spirit, Ultimate Hope, Ultimate Despair, Silence…. God is not a being, all-knowing, all-holy, almighty.

Nor is God a predetermined goal toward which history proceeds, but an increasingly and progressively evolving Eros, an erotic Spirit in creation itself, an élan vital, a vital, animating energy at the heart of the universe and within the human heart. God is an erotic wind and shatters all bodies that he might drive on, a divine eros always working through blood and tears. ODYSSEUS You remember the story where Odysseus, anticipating the Sirens sweet seductive song that has plunged previous sailors to their rocky deaths, plugs the ears of his shipmates with beeswax, but instructs them to tie him to the ship’s mast; he leaves his ears unplugged so that he might experience, might taste the full seduction longing of longing for the dark Abyss, staring into the face of seductive death, and to live, with courage, live. Odysseus, for Kazantzakis, becomes the archetype of the spiritual struggler, his great spiritual hero. Odysseus holds the two great opposing forces in a dynamic tension, a creative synthesis, as Kazantzakis puts it, “like that round fruit which two lips make when they are kissing” – there is the luminous, rational, and civilizing impulse of Apollo, the solar god; and there is the dark, intoxicated, primal breaker-of taboos, Dionysius, the god of wine and ecstasy. For Kazantzakis, Apollo is the supreme ideal of Western religion, to save the ego from annihilation, salvation from death, a personal god, symbolic of spirit, and embodied in the figure of Saint Francis of Assisi. And Dionysius (who originated in India) is the supreme ideal of Eastern religion, the achieve-ment of union through the dissolution of the ego into the Ground of all being, an impersonal energy, symbolic of the flesh, and embodied in the figure of Zorba. Both are necessary, both divine, both belong to Odysseus. — Odysseus soon tires of the idleness, the security, the “sweet Mask of Death” of family, country, friends, and duty. For, Kazantzakis tells us in this myth, the goal of life is not the safety and security of home, no matter how one defines home, although we dream of such security – “there’s no place like home” – but rather, the never-ending quest, the incessant voyage in search of home. So he sets off again. The true home is the struggle for home, the journey toward home. Kazantzakis’s Odysseus epitomizes the hero who “transubstantiates flesh into spirit,” but holds on to them both, because the spirit evolves in and through the flesh, because the spirit has no value apart from the flesh.

Whereas Homer’s Odysseus voyaged in search of his native land, Kazantzakis’ Odysseus left the security of his home in search of the evolutionary Eros that runs through the heart of the world, and his heart, which he called “God.” Home is the last temptation. Ithaca is the voyage itself, and the human heart is a restless heart. Anything or anyone – any ideology or philosophy or art, any religion or god that resolves that restlessness, no matter how beautiful or seductive, is nothing more than an illusion, an opiate that sedates the ever-ascending, ever-struggling human spirit. This is why Kazantzakis calls his Odysseus “a godslayer in search of God.” THE CRETAN GLANCE Kazantzakis writes: You triumph without killing the terrible bull because you think of it not as an enemy but as a collaborator; without the bull you could not become so strong or graceful or your spirit so courageous. This is a dangerous game and to play it you need great physical and spiritual discipline. The heroic and playful eyes, without hope yet without fear, which so confront the Bull, the Darkness, this I call “the Cretan Glance.” If you are able to dance with the tragic elements of life in both ecstasy and joy and to laugh in the face of this darkness – this is the highest calling of humanity, and this is where joy can be found. CHRIST AS ODYSSEUS And so, finally, we come to Kazantzakis’ figure of Christ, but not the Christ of the Bible or the Christian tradition. And even though he uses traditional Christian language, for Kazantzakis, “God” represents the evolutionary Rhythm, the Cry at the heart of Being Itself, and his Christ is recast, an Odysseus figure, eager to embrace the flesh, eager to embrace this world, so as to also, through it, embrace the deepest part of the flesh, the spirit. This is a Christ, Kazantzakis says in the Prologue to The Last Temptation of Christ, who: “The dual substance of Christ – the yearning, so human, so superhuman, of humanity to attain God, … to return to God, has always been a deep inscrutable mystery to me. This nostalgia for God, has opened in me large wounds and also large flowing springs. I was so moved that my eyes filled with tears…. I had never felt the blood of Christ fall drop by drop into my heart with so much sweetness, with so much pain…. “My anguish has been intense. I loved my body and did not want it to perish. I loved my soul and did not want it to decay.

This struggle breaks out in everyone, but most often it is unconscious and short-lived, because a weak soul does not have the endurance to resist the flesh for very long. That is why the mystery of Christ is not simply a mystery for a particular creed or particular culture or particular people. It is universal.” He continues: “The stronger the soul and the flesh, the more fruitful the struggle and the richer the final harmony. God does not love weak souls and flabby flesh. The Spirit wants to have to wrestle with flesh which is strong and full of resistance. It is a carnivorous bird which is incessantly hungry; it eats flesh and assimilates it. The supreme purpose of the struggle? Union with God…. (Last Temptation of Christ) I keep my heart flaming, courageous, restless. I feel in my heart all commotions and contradictions, the joys and sorrows of all life. But I struggle to subdue them to a Rhythm superior to that of the mind, harsher than that of the heart, the ascending Rhythm of the universe. The Cry within me is a call to arms. It shouts: ‘I, the Cry, am the Lord your God! I am not a refuge. I am not a home. I am not heaven. I am not the Father, nor the Son, nor the Holy Ghost. I am your General. And you, you are not my servant, nor a plaything in my hands. You are not my friend. You are not my child. You are my comrade-in-arms.’” (Saviors of God: Spiritual Exercises) And so, this ascent to which every human being is called, is not for the faint of heart. “What is most difficult?” he asks.” “That is what I want! Which road should I follow? The most craggy ascent! Follow me!” So in the end, all you’re left with is three souls, three prayers, three stages of the spiritual journey: “I am a bow in your hands, O Lord. Bend me lest I rot. Do not bend me too much, lest I break. Lord, bend me and who cares if I break.” At which stage are you? The trailer: